Parkinson’s disease is a common neurologic disorder that affects around 1% of people over the age of 65. In the United States alone, there are close to a million people with Parkinson’s.

We don’t know what causes Parkinson’s disease but we do know it results in a gradual loss of dopamine-producing cells in the brain. A loss of dopamine in the brain eventually causes the familiar movement symptoms of Parkinson’s: tremor, bradykinesia (slowness), rigidity (stiffness), and problems with gait and balance.

Treatment for Parkinson’s begins with medications. Most medications aim to replace the dopamine lost in the brain. We consider surgery for Parkinson’s when a patient has been using these medicines for several years and has started to develop “motor complications,” such as a rapid wearing off of medicines so that they have to be taken frequently throughout the day, dyskinesias (abnormal writhing movements that occur when dopamine levels from the medications are too high), and other movement symptoms like tremor and dystonia that aren’t improved enough with medicine. About 50% of patients develop these symptoms after being on dopamine replacement for 5 years. Surgery should be considered when these symptoms develop and affect your quality of life.

The surgery we performed historically for Parkinson’s was a pallidotomy, a procedure in which a small probe was introduced in the brain and used to burn a structure called the pallidum. Over time, we recognized that we could achieve even better results if we instead introduced a stimulator into the brain, so pallidotomy has largely been replaced by deep brain stimulation (DBS). DBS has the advantage of being flexible, allowing us to adjust the therapy as the patient’s symptoms change over time. It’s also reversible, meaning we can stop the therapy if we need to.

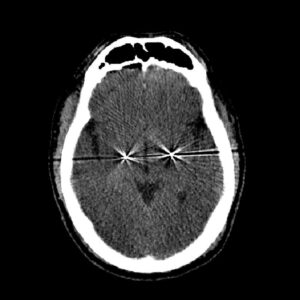

Below is a CT scan of the brain after placement of two DBS wires.

Today in the United States, the surgery that we perform most commonly for Parkinson’s disease is DBS. In a DBS procedure, I introduce a thin wire – just over a millimeter in diameter – into the brain. Patients cannot “feel” the electrical pulses of DBS, but they disrupt the abnormal brain rhythms that occur in Parkinson’s disease. DBS is very effective for the motor (movement) symptoms of Parkinson’s such as tremor, rigidity and dystonia, but it’s not effective for the non-movement symptoms (problems like memory loss, constipation, sleep disturbances, and loss of sense of smell).

The benefits of DBS include better motor function during the day, reduction in tremor, rigidity, and slowness, and improvement in quality of life. We’ve been using DBS in the United States for over 20 years. It is now the standard of care for patients with Parkinson’s who have developed motor complications.

A lot has changed in DBS in the last 20 years. We now have more sophisticated stimulation systems and implants, and we also have newer techniques for introducing the electrodes into the brain that are minimally invasive and more efficient, like the surgical robot (ROSA®) that I use.

DBS can be life-changing for patients with Parkinsons’. But DBS is not for every patient, so it’s important to meet with your neurologist and a surgeon to understand whether your symptoms are a good fit.

Candidacy and Risks of DBS

The decision to have DBS surgery is a careful one, and I spend a lot of time discussing with you, your family, and your neurologist about whether DBS is the right treatment for you.

In Parkinson’s disease, I consider DBS for patients who have had movement symptoms for at least four or five years, who had a good response to oral dopamine medications (levodopa or Sinemet), and who are now starting to have what are called motor complications. Motor complications are problems like rapid wearing off of your medication, dyskinesias (abnormal movements when levodopa/Sinemet is at a very high level in the bloodstream), and other movement symptoms like tremor and dystonia that are not responding to medicines.

In the case of essential tremor, good candidates for DBS are those who have had tremor for several years, have tried at least two medications for tremor, and continue to have a bothersome tremor that affects quality of life.

In the case of epilepsy, I consider DBS for patients who have focal seizures and have tried at least two or three different medicines and continue to have seizures that impact quality of life.

The main risks of DBS include infection, bleeding in the brain, and the possibility that your symptoms are not improved as much as you’re hoping. I reduce these risks with a rigorous infection control protocol, minimally invasive surgical tools, and, importantly, detailed discussions and testing with patients in advance of the surgery to understand who is likely to benefit the most.